The actual blog is here.

(more posts, comments, pages etc.)

Sogo Shosha

Date: 2020-09-09Not quite a whale, and pretty small investment, but interesting nonetheless. As usual, people are trying to read all sorts of things into this investment, from bullishness on Japan, bearishness on the U.S., the U.S. dollar, inflation hedge / exposure to natural resources etc. It almost feels like nobody ever reads anything Buffett writes. He doesn't base investments on themes like inflation or economic views or views on foreign currency exchange rates.

But anyway, one can only assume that Buffett feels that these Japanese trading companies are decent businesses with decent managements trading at attractive prices.

Let's just look at the big picture on these names. This table below is current as of early September 2020.

The other big problem is that a lot of large companies tended to want to rotate people every three years to give them a broad experience to prepare them for senior positions at HQ. I remember dealing with some of these employees in NY and was shocked at how things worked. They come over to NY knowing nothing about finance, for example, and they speculate using firm capital not knowing what they are doing. Of course, by the time they start to understand what is happening, they are 'rotated' out to London or somewhere else. So they barely get to understand anything before moving on and they eventually end up at the head office, not really knowing much.

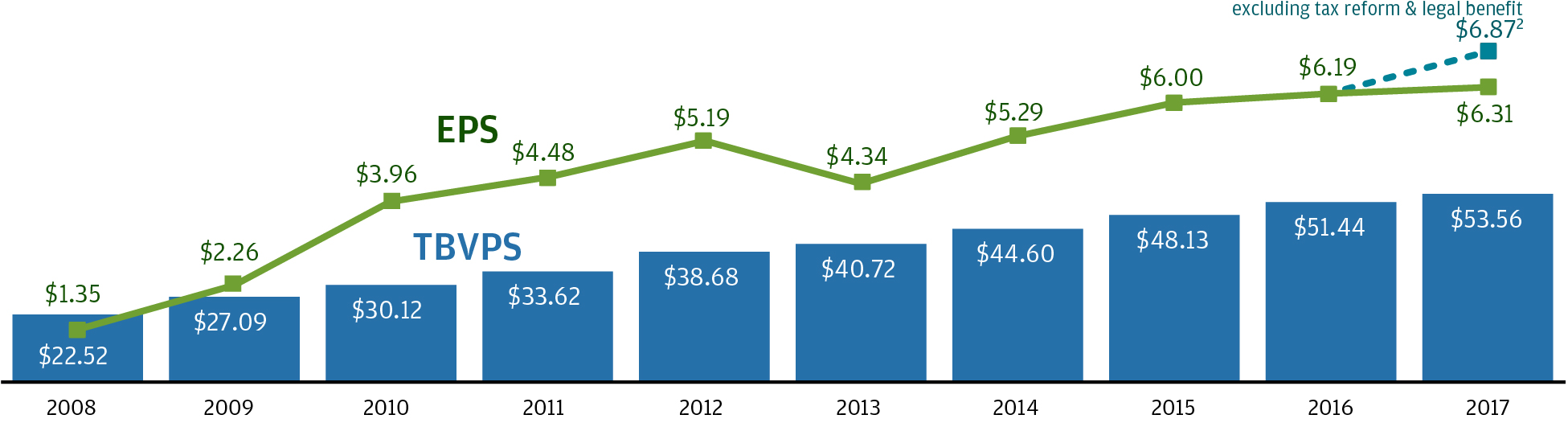

BPS Growth of Buffett's Shoshas

It's hard to see, but the below tables are what's at the bottom of the above table. They show the stock price and valuation of the stock every year from 2011 through 2020. And you can see that the stock has always been really cheap; single digit P/E's and trading at around BPS.

Despite this, their historical returns are pretty decent.

A cheap stock that has grown nicely over time is sort of a no-brainer, if you believe in the quality of the earnings and accounting values of book.

Trading companies are hard to analyze. I have spent time on them in the past, and they were usually just big, black boxes. They have evolved over the years from a purely import / export business to more of an investment business. A lot of investments, though, are related to their client businesses. For example, a company might buy a farm that produces products to export to Japan, or may invest in an oil field that will export oil to Japan etc.

There was a little block in the 2020 annual report explaining how they differ from private equity funds.

Here's another snip showing the ROE of Itochu going back to 2011. This is very unJapan-like, with double-digit ROEs for the whole period.

...and here's a nice snip showing labor productivity. But I am not so sure how relevant this is as they are investing more. Investments will increase profits and may not necessarily increase number of employees. Kind of like Berkshire Hathaway; not all employees are directly related to the revenues the holdings produce.

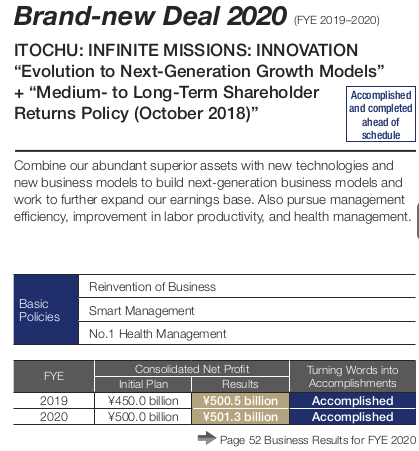

...and here is a snip of all the medium-term plan targets and results in the recent past. They have achieved most of their goals.

Is Buffett Really Bearish?!

Date: 2020-08-20So, with Buffett dumping airlines, JPM and not jumping into the markets in March, is he really all that bearish? His cash keeps piling up to the frustration of long time Buffett fans.

BRK Balance Sheet Stuff

Tsunami etc.

Date: 2020-08-19The Economists Go out -- The Psychologists Come InI have already commented on the strange tendency of the supposedly forward-looking financial community so often to fail to recognize a changed set of circumstances until the new influence has been in existence for years. I believe this is why the man who attempted to forecast the course of general business was regarded as so important a factor in the making of investment decisions during all of the 1940's and much of the 1950's. Even today, a surprising number of both investors and professional investment men still believe that the heart of a wise investment policy is to obtain the best business forecast you can. If the outlook is one of expanding business, then buy. If the outlook is for a decline, sell.Many years ago there was probably considerably more merit to such a policy than there could possibly be today. The banking structure was weaker. There was no assurance it would be shored up by the government in times of real trouble -- a process bound to produce a massive dose of inflation. There was no tax system of a type that can hardly fail to produce strong inflationary spending whenever business (and therefore federal tax revenues) are at abnormally low levels. No public opinion had crystallized to assure that whenever business levels dipped sharply, the government would take strong countermeasures to stem the tide. Finally, the industrial base was much more narrow. The large number of industries in today's complex economy that bear little relationship to each other in their basic characteristics probably assures that even without the actions of government, modern business recession would be somewhat less severe than its former counterpart. Some industries would be enjoying unusual background conditions enabling them to expand, while the majority might be in a declining phase. This tends somewhat to stabilize the economy as a whole.All this means that a depression is of less significance to the investor than it was many years ago. It does not mean knowing what business is going to do would not be quite useful information to have. But having such information is not vital for obtaining magnificent results from common stock investments. Simple arithmetic should show this. When a stock market decline coincides with a fairly sizable economic slump as happened in 1937 to 1938 or 1957 to 1958, most stocks sell off from 35 to 50 percent. The better ones then recover when the slump ends and usually go on to new high levels. Even in the greatest slump of all time, only a small percentage of all companies failed, that is, went down 100 per cent. Most of these companies were companies which had had fantastic amounts of debt and senior securities placed ahead of their common. After one of the wildest speculative booms ever known, much of it financed by borrowed money, the average stock slumped 80 or 90 per cent. In contrast, when stocks rise over a period of years, even the most casual study of stock market history shows many figures of a very much greater order of magnitude. Compared to the temporary declines, usually of 35 to 50 per cent, that frequently accompany depressions, the outstanding stocks (those of the unusually well-run companies that have maneuvered themselves into growth fields) go up several hundred per cent, stay at these levels, and then go still higher. Many can be found for which a decade's progress can be measured in multiples of 1000 per cent rather than 100 per cent....From the standpoint of obtaining results, I have noticed that investors who place heavy emphasis on economic forecasts in the making of investment decisions usually fall into one of two main groups. Those who are inclined to be cautious by nature can nearly always find an impressive sounding forecast that for quite plausible and persuasive reasons makes it appear that important economic difficulties lie ahead for the business community. Therefore, they seldom take advantage of opportunities when they present themselves and, on balance, these missed opportunities mean the economic forecasts have done them considerable harm. The other group are the perpetual optimists who can always find a favorable forecast to satisfy them. Since they always decide to go ahead with whatever action they are considering, it is hard to see how all the time they spend on business forecasting does much good.More and more investors are coming to recognize the wisdom of making their decisions about common stocks largely on the basis of such outright business factors as appraisal of the quality of the management and the growth potential of the individual company's product line. These things both can be measured with a fair degree of preciseness and have a far greater influence on how good a long-range investment will be...

So...

Anyway, this is a fascinating time to be living in. This pandemic is really terrible and I hope we at least find some sort of treatment to take death off the table. I feel this is the key to normalization rather than vaccines. Of course, a vaccine would be great, but it is probably unrealistic to expect one to come within a year. If we can figure out how to treat the worst cases, and this treatment becomes widely available, this would sort of turn Covid-19 into something like the flu.

But who knows, really.

As for stocks, there is certainly a lot of trading opportunities, but for us long term investors, I would stick to things that have secular growth potential. I don't really feel that excited about buying the dip on something in a long term downtrend. Not to say those can't be great trades. I would rather buy the dip on things in long term uptrends. If things are in secular downtrends but got a bump up due to this, then that's probably a great time to sell.

Wow!

Date: 2020-05-20But if you look at their income statements and realize that their revenues are down 90% and may be down for a year or more, it's hard to imagine them surviving. Most of them will be out of business by the end of the year or long before that. The government will have to bail them out, but that will be costly. Either they will have to take on a lot of debt that will take years to pay off, or they will have to issue a lot of equity, basically wiping out current shareholders.

It may be helpful to elaborate our definition from a somewhat different angle, which will stress the fact that investment must always consider the price as well as the quality of the security. Strictly speaking, there can be no such thing as an investment issue in the absolute sense, i.e., implying that it remains an investment regardless of price. In the case of high-grade bonds, this point may not be important, for it is rare that their prices are so inflated as to introduce serious risk of loss of principal. But in the common-stock field this risk may frequently be created by an undue advance in priceso much so, indeed, that in our opinion the great majority of common stocks of strong companies must be considered speculative during most of the time, simply because their price is too high to warrant safety of principal in any intelligible sense of the phrase. We must warn the reader that prevailing Wall Street opinion does not agree with us on this point; and he must make up his own mind which of us is wrong.Nevertheless, we shall embody our principle in the following additional criterion of investment:

An investment operation is one that can be justified on both qualitative and quantitative grounds

| Anheuser-Busch Inbev ADR | 0 | 0.00% | 13,000 | -13,000 | -100% |

| CDK Global Inc | 0 | 0.00% | 176,897 | -176,897 | -100% |

| Discovery Communications | 0 | 0.00% | 117,000 | -117,000 | -100% |

| Dollar Tree Inc | 0 | 0.00% | 123,100 | -123,100 | -100% |

| Hasbro, Inc | 0 | 0.00% | 364,000 | -364,000 | -100% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 0 | 0.00% | 68,000 | -68,000 | -100% |

| Rockwell Automation Inc | 0 | 0.00% | 140,100 | -140,100 | -100% |

| Scotts Miracle-Gro Co | 0 | 0.00% | 422,000 | -422,000 | -100% |

| Unilever PLC ADR | 0 | 0.00% | 1,527,600 | -1,527,600 | -100% |

| United Health Group Inc | 0 | 0.00% | 599,000 | -599,000 | -100% |

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC

Filing Date: 2020-05-15

| Name | dollar amt | %port | #shares | change | %chg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APPLE INC | 62,340,609 | 35.52% | 245,155,566 | | |

| BANK AMER CORP | 19,637,932 | 11.19% | 925,008,600 | | |

| COCA COLA CO | 17,700,001 | 10.09% | 400,000,000 | | |

| AMERICAN EXPRESS CO | 12,979,391 | 7.40% | 151,610,700 | | |

| WELLS FARGO & CO NEW | 9,276,210 | 5.29% | 323,212,918 | | |

| KRAFT HEINZ CO | 8,056,205 | 4.59% | 325,634,818 | | |

| MOODYS CORP | 5,217,658 | 2.97% | 24,669,778 | | |

| JPMORGAN CHASE & CO | 5,196,030 | 2.96% | 57,714,433 | -1,800,499 | -3% |

| US BANCORP DEL | 4,563,233 | 2.60% | 132,459,618 | | |

| DAVITA HEALTHCARE PARTNERS I | 2,897,549 | 1.65% | 38,095,570 | -470,000 | -1% |

| BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON CORP | 2,686,487 | 1.53% | 79,765,057 | | |

| CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS INC N | 2,367,684 | 1.35% | 5,426,609 | | |

| VERISIGN INC | 2,307,964 | 1.32% | 12,815,613 | -137,132 | -1% |

| DELTA AIR LINES INC DEL | 2,050,935 | 1.17% | 71,886,963 | 976,507 | 1% |

| SOUTHWEST AIRLS CO | 1,910,218 | 1.09% | 53,642,713 | -6,500 | 0% |

| VISA INC | 1,701,823 | 0.97% | 10,562,460 | | |

| GENERAL MTRS CO | 1,551,872 | 0.88% | 74,681,000 | -319,000 | 0% |

| LIBERTY MEDIA CORP DELAWARE | 1,446,433 | 0.82% | 45,711,345 | -240,000 | -1% |

| COSTCO WHSL CORP NEW | 1,235,572 | 0.70% | 4,333,363 | | |

| MASTERCARD INC | 1,192,040 | 0.68% | 4,934,756 | | |

| AMAZON COM INC | 1,039,786 | 0.59% | 533,300 | -4,000 | -1% |

| PNC FINL SVCS GROUP INC | 880,431 | 0.50% | 9,197,984 | 526,930 | 6% |

| UNITED CONTL HLDGS INC | 699,073 | 0.40% | 22,157,608 | 218,966 | 1% |

| SIRIUS XM HLDGS INC | 654,149 | 0.37% | 132,418,729 | -3,857,000 | -3% |

| KROGER CO | 570,475 | 0.33% | 18,940,079 | | |

| M & T BK CORP | 556,665 | 0.32% | 5,382,040 | | |

| AMERICAN AIRLS GROUP INC | 510,871 | 0.29% | 41,909,000 | -591,000 | -1% |

| GLOBE LIFE INC | 457,278 | 0.26% | 6,353,727 | | |

| LIBERTY GLOBAL PLC | 434,229 | 0.25% | 26,656,968 | -481,000 | -2% |

| AXALTA COATING SYS LTD | 415,689 | 0.24% | 24,070,000 | -194,000 | -1% |

| TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDS LTD | 384,248 | 0.22% | 42,789,295 | -460,000 | -1% |

| RESTAURANT BRANDS INTL INC | 337,782 | 0.19% | 8,438,225 | | |

| STORE CAP CORP | 337,425 | 0.19% | 18,621,674 | | |

| SYNCHRONY FINL | 323,860 | 0.18% | 20,128,000 | -675,000 | -3% |

| STONECO LTD | 308,410 | 0.18% | 14,166,748 | | |

| GOLDMAN SACHS GROUP INC | 296,841 | 0.17% | 1,920,180 | -10,084,571 | -84% |

| SUNCOR ENERGY INC NEW | 236,195 | 0.13% | 14,949,031 | -70,000 | 0% |

| OCCIDENTAL PETE CORP | 219,245 | 0.12% | 18,933,054 | | |

| BIOGEN INC | 203,440 | 0.12% | 643,022 | -5,425 | -1% |

| RH | 171,638 | 0.10% | 1,708,348 | | |

| JOHNSON & JOHNSON | 42,893 | 0.02% | 327,100 | | |

| PROCTER & GAMBLE CO | 34,694 | 0.02% | 315,400 | | |

| MONDELEZ INTL INC | 28,946 | 0.02% | 578,000 | | |

| VANGUARD INDEX FDS | 10,183 | 0.01% | 43,000 | | |

| SPDR S&P 500 ETF TR | 10,155 | 0.01% | 39,400 | | |

| UNITED PARCEL SERVICE INC | 5,549 | 0.00% | 59,400 | | |

| PHILLIPS 66 | 0 | 0.00% | 227,436 | -227,436 | -100% |

| TRAVELERS COMPANIES INC | 0 | 0.00% | 312,379 | -312,379 | -100% |

| Total | 175,485,996 |

Plus, interest rates are now 0% all the way out to 5 years, and 1% to 20 years. That's going to be painful, and makes BRK's float basically worthless. Yes, this may be temporary, but we have been saying that for more than 10 years now. I have always suspected we will follow Japan in terms of interest rates. I didn't expect a pandemic to cause rates to go to zero, though.

I still think BRK, MKL and others are great investments for the long haul, but there are serious issues for them out there for sure.

Banks

JPM and other banks are going to take some huge credit losses. There is no way around that. One rule of thumb is that credit card losses will follow the unemployment rate. Unemployment got up to 10% during the financial crisis, and sure enough, JPM's credit card charge-offs peaked at 10% or so. Total charge offs were 5%, I think, back then.

Unemployment is now over 15%, and headed to 20%. JPM has $160 billion in credit card loans, so credit card charge-offs can get over $30 billion. Total credit losses may get to 10% and they have around $1 trillion in loans outstanding. Who knows, really.

JPM is still the best managed big bank and they will get through this for sure, but they face some very serious problems. I think the view expressed during the 1Q conference call (expecting rebound in second half of the year) is way too optimistic.

Even if we start to reopen the economy, we can't really have a real recovery as a lot of events won't come back, and restaurant / bars / retailers will run at 30-50% capacity.

An interesting thing to look at is Sweden. They didn't have a hard lockdown like the U.S. and European countries, but their economy is taking a hit anyway. Reopening the economy doesn't mean we are all going to go back to the way we were right away. Many people tell me that they won't change anything even if the economy reopens until they get a vaccine. This could be years away.

I tend to believe things will normalize when we get a treatment that makes Covid-19 far less fatal. If we take that off the table, people will start to get back to normal.

I have no idea about these things, but I tend to think the odds of us finding a treatment is far higher than us finding a vaccine (there is a chance we may never find a vaccine).

Anyway, the mitigating factor to the above bank credit disaster is the amount of money being injected into the economy. I don't know if people are going to use their stimulus / Covid-19 help checks to pay off their credit card (they seem not to be paying their rent), but it will have some positive impact on bank credit, I assume (and hope). Well, but don't assume because...

So when the markets move, I think we have to look by sector, and by stock, to see what they're expecting. It makes no sense to look at the index itself.

I haven't owned any retail stocks in a long time (except BRK, which is the closest thing to a retailer I own), and the only restaurant stocks I own are CMG, QSR and SHAK. Well, SHAK was never cheap so it's a token position that is not significant; it's more of a moral support, I like this company, kind of position. CMG was a large position that I scaled back and had to do again as it went over $1,000. It's not a cheap stock, and I have no idea why it's above $1,000; maybe they are going to take market share after many of their competitors go out of business within a few months). Oops, after writing this, I just realized I do own Costco. So I lied. I own Costco and have no problem with it. I will hold on to it. Yes, it's expensive, but I really like the business for all the reasons we've all heard already a gazillion times.

Who Cares What Mr. Market Thinks!

Date: 2020-03-02So, the market has gone crazy. People ask me about the market and the impact of the COVID-19 and I keep saying it doesn't matter. But with the market acting like this, it's hard for people to agree with me. The markets make the news, the market creates the sentiment etc. and I can't fight that. That's OK, as it doesn't really matter to me.

But I had a really interesting conversation recently, and I did some illustrative work and thought it was interesting so decided to make a post about it.

Every time people worry about these things, whether it's a trade war, Brexit, 9/11, fiscal cliff, coming recession/depression, war or whatever, I say the same thing. If something is not going to have a long term impact on the intrinsic value of businesses, it doesn't matter.

If you own a restaurant on a beach and the weather forecast shows a hurricane approaching, are you going to rush to sell the restaurant before the hurricane hits? Are you going to lower the selling price because you know the hurricane is going to hit and you are going to lose a few days or possibly weeks of business? Of course not! So why would you do the same with stocks?

I think most will agree that COVID-19 is temporary. We just don't know how bad it's going to get before we get it under control (I still think there is way more COVID-19 even here in NYC than anyone thinks, because frankly, people are just not being tested. Plus I don't think the government is going to be truthful about this; I was living in Battery Park City during and after 9/11 and the EPA lied to us about the safety of the air. Christy Whitman admitted she lied to us about the safety of the air (she denies knowing the truth at the time, but I don't believe that at all). Forgot who, but someone said that the government had to balance the risk of causing a panic and the abandonment of downtown NYC (to the detriment of real estate prices downtown) with the 'minor' risk of people getting sick from inhaling toxic fumes. This is especially true when the known risks were also known to be far off into the future, long after elected politicians are out of office (so won't need to take any of the heat). So this was not really about public safety but more about social control. Not that different from China, are we?)

But in my recent discussion, I had trouble getting across that the intrinsic value of the restaurant is not going to be impacted by the coming hurricane. Yes, they will lose business, and will probably have to repair some damage (even though that should be insured). Of course, in the hurricane example, there is a possibility that it wipes out the whole beachside town and it takes years to rebuild. But most market exogenous events in the past ten or twenty years weren't of the magnitude to destroy everything (in aggregate) for years.

Current P/E

So when I say it doesn't matter about COVID-19, I don't mean to say there will be no impact. I just mean that there is no impact on the intrinsic value of businesses in general 5, 10 or 20 years out.

If people value stocks on current P/E ratios, then yes, there will be an impact on stock prices. If you value a stock at 10x P/E and think it's going to earn $1 this year, but COVID-19 will cause it to earn $0.50 instead, then you might think the stock is only worth $5.00 instead of $10.00. But if you think this dip in earnings is temporary, you would still think the stock is worth $10.00.

P/E ratios are just a short-cut to calculating future discounted cash flows, so it sort of makes no sense to price a stock on current year estimates if there is a one-time factor involved.

Intrinsic Value

So this is the part I had a hard time describing. I guess non-financial people (unfortunately including many in the financial press) have a hard time grasping the idea that intrinsic value of a business is the discounted present value of all future cash flows. This person argued that the market looks only at earnings over the next year or two, but not fifty years out. Yes, this is true. But intrinsic value has nothing to do with what the market is looking at. Intrinsic value is a mathematical truth as long as the inputs are correct (or reasonable enough). Intrinsic value is 100% independent of Mr. Market's opinion. Well, Mr. Market does set the discount rate to some extent.

When people slap a P/E ratio on a stock, they are basically discounting all future cash flows back into the price of the stock; they may just not know it or understand it. The P/E ratio is just a shortcut valuation method.

If you value a stock at 10x earnings, you are basically pricing in a 10% earnings yield going out into perpetuity.

So first of all, we have to understand that regardless of what the 'market' is looking at, or what the pundits say on TV, a business is simply worth the present value of all future cash flows. We can argue whether that's earnings, dividends, free cash flows or whatever. But the idea remains the same.

Here's the thing I did to try to illustrate how non-eventful recessions and exogenous events are to the intrinsic value of businesses in general (but alas, this illustration failed to get the point across in this case even though the person is a highly trained engineer! No wonder why Mr. Market is so irrational!).

Simple Model

So, here's the illustrative model. Let's say the market has an EPS of $10/year, and the discount rate is 4%. In this table, I just took the earnings for the next 10 years and discounted it back to the present at 4%, and then added a residual value at year 10 based on a 25x P/E ratio (or 4% discount rate), and discounted that back to the present and added them together. Of course, this would give the market a present value of 250.

I think most of you have no problem with any of this. For illustrative purposes, the details don't really matter, and I have no earnings growth built in here either.

Now, let's say COVID-19 causes the global economy to stop for 3 months, and companies earn no money at all for three months. Of course, many businesses will lose money (retailers, hotels, airlines), but others will continue at a lower rate but may not lose money in aggregate. Remember, the S&P 500 (and predecessors) has shown a profit every single year since the 1800s, and that includes the great depression, world wars, great recession etc. So this is not a stretch.

Plugging in $7.50 for year one earnings instead of $10.00 would negatively impact intrinsic value of the market for sure. There is no doubt about it.

Let's quantify that. I copied the above table into another one so we can look at it side-by-side.

If the above scenario holds, the intrinsic value of the market would go down less than 1%.

Way too optimistic you say? OK, so let's say the S&P companies make no money for six whole months. What does that do to intrinsic value?

Let's take a look!

This scenario would dent intrinsic value by less than 2%.

OK, screw that. Too optimistic. Let's say that the economy is wiped out for a whole year, and the S&P companies make no money for a whole year. Remember, this didn't happen even during the great depression or great recession (or during the 1918 flu etc.).

Still too optimistic? OK. Zero earnings for two years, then.

Ah, now we are starting to hurt the market. With zero earnings for the first two years, intrinsic value is knocked down by 7.5%. Ouch. That hurts.

Here are some more:

So, with the market down more than 12%, it is like the market is discounting no earnings for the next four years! Nuts!

When the pundits say that the market is or isn't done discounting the risk of COVID-19 or a coming recession, you can see how that sort of comment is total nonsense. It is based on Keynes' beauty contest. They are just saying that people didn't expect a recession or negative event earlier this year, and now these things are here so the market therefore must go lower as the market lowers their expectations.

But this has nothing, really, to do with intrinsic value or expectations thereof. It is just based on pundits guessing what Mr. Market would do based on the headlines.

Of course, I would be the first to admit that if an event did occur that would cause the S&P500 companies to not earn any money for a whole year, two years or three years, it would cause a drop in the market far in excess of the decline in intrinsic value. That would have to be quite a scary event!

Again, this is just a simple illustrative model. There are other reasons why the market can be down. The market may simply have been overly optimistic / overvalued, and this has triggered a 'normalization' of valuations. Maybe the market needs to increase the discount rate to account for the increasing risks that were not considered in the past. Maybe this will actually cause some sort of permanent reduction in the profitability of corporations in general going forward.

But remember, we all had the same thoughts every time something happens. We all see some permanent negative change that explains a lower stock market. For example, after 9/11, the thought was that the world would never be the same, and that increased security measures will permanently reduce global growth potential and profitability.

Again, the market makes the news, and the market creates the explanations, not the other way around. We all try to model the facts to explain what is going on in the market to maintain the two illusions that 1. the market is always right, and 2. that we know what's going on. We wrap the market volatility tightly into these rational-sounding wrappers, pleased at having figured it out, secure in the knowledge that we know what's going on.

Conclusion

OK, so I lied. The above tables clearly show that there is a negative impact on intrinsic value by even temporary business interruptions. But the magnitude is not nearly as much as the market usually moves.

Index arbitrage traders make money because the futures contract fluctuates much more widely than the fair value of the contract. Debt / credit traders make money because credit spreads fluctuate (or at least used to) much more widely than the credit quality of companies. And value investors make money because stock prices fluctuate much more widely than intrinsic value of the underlying businesses.

Of course, I am not calling a bottom in the market, or trying to say that markets won't or shouldn't fluctuate based on the headlines. We can be pretty sure there will be more wild days to come. Markets can be up or down 1000, 2000 points on news. I still expect photos of empty streets in NYC at some point before this is over with the market down a lot on those images. NYC is only starting to test this week, so when more cases are found, subways will be empty too, and of course the market will be down on that.

But I have no idea, actually. It's sort of what I expect (and have been expecting since early February).

On the other hand, check out the VIX index. In my trader days, this was my favorite indicator. As Munger says, always invert. You don't usually make money being short in a market with the VIX at a high level, and it's as high as it's been in the past few decades. This is no guarantee that the market can't go lower, of course.

But anyway, who cares what Mr. Market thinks!

Coronavirus, Munger etc.

Date: 2020-02-14Munger

Munger is looking and sounding great at the DJ annual meeting (I wasn't there; just watched the video). His 'wretched excess' seems to be more about private equity and venture capital than the public stock market. In fact, he said that tech stocks now are not like the Nifty Fifty stocks (he mentioned Home Sewing (?) trading for 50x earnings, and said that the current big tech companies are better businesses).

TSLA

Munger also said he would never buy or short TSLA. As I wrote in a response somewhere on this blog, I can't believe how many people got caught in a short squeeze on this stock. If people don't care about the valuation of a company, then obviously, a really expensive stock can get much more expensive. Trying to short that is like trying to short soybeans during a drought. You know with 100% confidence that the price will mean revert at some point, but there is no way to tell when it will revert and how high it can get before reverting. I saw this in Japan in the 1980s, in the U.S. in the late 1990s etc.

Bubble

I've said this here many times before, but for the stock market to be in a real bubble, at these interest rates, the P/E ratio would have to get up to 50x or some such. Who knows, this might even happen. One of the greatest traders of all time recently said that this might happen; the NASDAQ could double from here if we have another late 1990s-type bubble, which is possible with the current, ongoing massive stimulation combining low rates and huge budget deficits. How can this massive stimulation on a historical scale not be matched by an equivalently massive bubble?

Of course, I would not invest with that expectation, but if it happened, it would not surprise me at all. Remember, from my previous analysis, I would find it completely normal and not at all out of line if the market P/E averaged 25x over the next 10 years... and that may include times the market trades at 50x P/E, and times it trades at 10x P/E. But we just can't know when these levels are reached; only that it is probable that they will be reached.

Again, this is not my prediction at all; I would not invest expecting such an outcome. I am just making a single statement that seems reasonable from the data I've seen.

Coronavirus

The market seems to fluctuate with each breaking news about the coronavirus, but I view it as a non-event. As value investors, we care about what a business is going to be worth five, ten years out, so it doesn't matter how bad this coronavirus gets. Well, unless it gets really, really bad. I didn't take any action, but my instinct during SARS was to just buy all the Asian stocks that were hit hard, especially airlines (Cathay etc.).

I feel the same way now. If the market tanks further on coronavirus (well, I know we are at highs recently but...), just stay sane and buy what becomes cheap and available. As Munger says, keep your head as others lose theirs (well, he was quoting Kipling).

But wait, I am no expert, so let's just say this does get really bad, like the 1918 Spanish Flu. That was bad. 50 million people died around the world back then including 675,000 Americans. Quick googling shows that the world population at the time was around 2 billion, and the U.S. population was around 100 million. So the flu killed 2.5% of the world population and 0.7% of the U.S. population. A similar event now would kill 193 million people around the world, and 2.3 million Americans.

That would be quite a shocking event. By the way, did you know that the flu has killed 12,000-61,000 per year since 2010 in the U.S.? Between 291,000 - 646,000 people die of the flu around the world each year. I don't mean to trivialize the coronavirus. We have to do what we can to stop it, of course.

Anyway, let's take a look at the economic impact of such a worst case scenario (well, I know, there can be worst cases than 1918, of course. I am a big fan of The Walking Dead, 28 Days Later, World War Z, Shaun of the Dead etc... )

This is the chart of deaths from the 1918 flu from the CDC website. Not easy to read, but I think the deaths peaked in the 4th quarter of 1918.

Now, hold this image in your head while you look at the next chart. I couldn't find anything to take a close-up view of this, but if you look at GDP from 1915-1920, there is no real visible blip.

Same with the stock market. Close-up views of the market between 1915-1920 also doesn't really show much worth responding to in terms of stock market activity. There really is no visible or actionable blip as far as I can see. Again, you can google for a close-up and you won't really find anything, I don't think.

Of course, coronavirus is a terrible thing and it is disrupting a lot of people's lives. There is no doubt there is a huge impact to many people all over the place.

But as investors, we have to keep our cool and not freak out over every new data point. There is no doubt that the numbers will rise over time, and I honestly don't believe at all that there is no coronavirus in NYC, for example. I think the odds of that are ZERO. There is no way that there is no coronavirus here. It's just that we don't know yet how many we have, as apparently, NYC still doesn't have a test for it so has to send samples down to Atlanta. Plus, most people I know do NOT go to the hospital for a fever and a cough. I certainly don't, unless there is a reason to do so, or else I am told to.

So honestly, nobody knows how much is already here in NYC, and how much it is spreading. We won't know for a long time, and we may never know.

This can get worse, may peak out soon, or they may come up with a vaccine soon too. Who knows.

Many argue that the globalized supply chain will make the impact of this flu worse than previous cases, but there are positives about globalization too, like communication and technology, that might make responding to the virus much more effective. But again, who really knows.

I just don't think it's worth spending too much time on.

Bullish

Well, actually, I am not bullish or bearish. I just am. But if I had to guess, I tend to think these 'events' are hugely bullish. This is sort of true for most exogenous events. Why? Because governments / central banks tend to overreact. We are so afraid of negative economic impacts that they will overcompensate. This often leads to bubbles, which is usually not good.

Think about the bubble in Japan in the 1980s; much of that was a response to the yen-shock (Plaza accord of 1985); the fear that the strong yen will destroy the Japanese economy contributed to the bubble in the late 1980s there. In fact, the same sort of FX bickering between the US and the UK contributed to the 1920s bubble. Greenspan's fear of Ravi Batra's Great Depression contributed a lot to the bubble in the late 1990s (and the various meltdowns from Russia, Turkey, Asia, LTCM etc. all of these contributed to the bubble as the Central Bank(s) overcompensated).

This happened again after the Great Recession, and will now happen again due to fears that the coronavirus will plunge us into a recession (and was sort of happening due to fears that the trade wars will kill the economy).

So every time something bad happens, it has just been enormously bullish, every time. Of course, this can't go on. At some point, we will start pushing on a string, and the old tricks will stop working. That is also a certainty. And bubbles will pop every now and then, but only after a bubble becomes a real bubble, usually.

But, we can't really know when this (the end) will happen. Unless you are sure that we have reached the end of the line, you have to asssume that these negative events will just be hugely and incorrectly overcompensated for resulting in huge rallies everywhere.

Anyway, this is not really a bullish proclamation on my part. I will remain neutral (but invested), but just an observation.

Malone Interview (CNBC), Iger Book, Bubble Watch

Date: 2019-11-30People keep talking about how crazy the market is, up more than 25% this year. It's a big year to be sure. But on the the other hand, even though the market has been decent in recent years, it hasn't been particularly bubblicious.

To put the 25% return into context, I think it's a good idea to look at it over 2 years or 3 years. Since the end of 2017, for example, the market has return an annualized 8.4%/year. Pretty good to be sure. Since the end of 2016, its up around 12%/year. Going back five years, it's up 8.8%/year (these figures exclude dividends).

Not bad at all, but not bubble-like either. If you were going to train an AI machine to look for bubbles, you would look at valuations (interest rate adjusted), sentiment etc. But one of the biggest factors that I would include would be historical returns over various time frames; strong performance reinforces the positive loop of increasing positive sentiment -> higher prices -> better-looking historical returns -> increasing optimism and 'proof' (both statistical and social) of the greatness of stocks etc.

The 10-year return is10.9%/year,but that's off a depressed level due to the great recession. Over 20 years, the market has gone up only4%/year.

Here is a table of the S&P 500 index change over various time periods.

S&P 500 Annualized Returns Through November 2019 (excl. dvd)

1-year return: 25.30%

2-year return: 8.39%

3-year return: 11.95%

4-year return: 11.34%

5-year return: 8.81%

10-year return: 10.91%

20-year return: 3.87%

30-year return: 7.55%

50-year return: 7.31%

S&P 500 Annualized Returns Through December 1999 (excl dvd)

1-year return: 19.53%

2-year return: 23.05%

3-year return: 25.64%

4-year return: 24.28%

5-year return: 26.18%

10-year return: 15.31%

20-year return: 13.95%

30-year return: 9.67%

50-year return: 9.36%

This is pretty insane. The annualized return over 5 years to December 1999 was 26%! And we are sort of freaking out that the market is up over 25% year-to-date in a single year, and not even double digits annualized over 2 years.

So anyway, that's why it doesn't really feel like a bubble. People aren't quitting their jobs (to trade stocks), buying new cars (with their capital gains), bigger houses and things like that we saw back in 2000. Most people I talk to still tend to hate stocks, the financial crisis still fresh in their minds.

Iger Book

I just finished the Iger book, and it was also a pretty great read. Iger seems like a genuinely nice guy. CEO's tend to have an image of not being nice guys, so it's great to see someone like him make it to the top. It's possible to be decent, honest and honorable and still do well.

Buffett did mention DIS as one of the well-managed companies (along with GE at one point); his relationship with DIS goes back to when DIS bought Capital Cities during the Eisner years (and Iger was working for Thomas Murphy / Dan Burke). And I think it goes even further back than that, actually.

It's fascinating to read about the events that we've been reading about in the newspapers from the people that were involved. This one involves Buffett / Murphy / Burke, Steve Jobs, George Lucas, Pixar and a lot of what is going on in media today. This connects (unintended) to the Malone interview below.

Anyway, this book is a quick read so go get it. By the way, I have not subscribed to Disney+ yet as I am big into Netflix and there is just so much stuff there that I can barely scratch the surface of what I want to watch (by the time I cancelled the DVD part of my Netflix subscription, I had more than 400 DVD's in the queue). My favorite things are the European cop dramas (French, Belgian, German, Norwegian etc.), the Indian and Japanese shows, and of course many U.S.-based shows too. I just watched The Irishman which is really good (creepy is the special effects to make these close-to-80 year olds look middle-aged), but at the same time I also thought, gee, do we really need another wise-guy movie?

OTT Tangent

People keep talking about the competition in direct-to-consumer streaming and how increasing competition will hurt Netflix etc. This is probably true to some extent; when Netflix was the only game in town, that's one thing, but with many participants jumping in, that's another story altogether.

On the other hand, when you think about it, this is not really an either-or world. People aren't going to sit there and debate whether to switch from Netflix to Disney+ or Apple. Netflix charges $14/month or some such thing, and Disney+ is even cheaper.

A lot of people are still paying $100/month or more for the conventional video package ( I dropped that a couple of years ago mostly because I don't watch most of the channels (ESPN, for example), but what bothered me even more was that they were charging me $14/month for each cable box in the house, which seemed ridiculous to me. Those things can't cost more than $100 (look at Roku at $20; and if it actually does cost more than $100, it's for functionality that I don't need), and they are charging $14/month forever; this makes absolutely no sense.

If you cut the chord, you have $100/month in video budget you can allocate (you still need to pay for the internet), so you can have Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, HBO and a few other things and still be under $100...

Malone Interview

There are a few annual events that are really exciting to me. Of course the Berkshire annual meeting (I just watch the video later), annual report, JPM annual report etc.

And another one of those is the CNBC John Malone interview by David Faber. Faber is one of the few people (of the reporters/anchors), if not the only one, who seems to understand the market and business.

Anyway, I jotted down some notes while watching the recent interview (done during the Liberty Media investor day). This is not everything, though, but a large part of it. He also talked about regulation, GOOG etc, for example, so go check out the video.

Here are Malone's thoughts on various topics:

Who is best positioned in streaming right now?

Malone answered by rephrasing the question to, "Who will be around in five years?"

Disney and Netflix.

DIS

Disney has great content, a great global brand, but doesn't have a large direct relationship with customers so must piggy back on those who do, like Verizon.

NFLX

Netflix, so far in the lead, good base / revenue stream.

AAPL

Apple may surprise. Slim content, but has great distribution in their direct customer relationships. They offer free for one year to buyers of AAPL products etc...

AAPL has optionality; see how it goes and decide how much they want to spend (how much they can afford).

HBO, AMZN

HBO is a decent service, but doesn't have the revenue stream to match Netflix.

AMZN has a totally different monetization strategy so... not primary biz.

Content is for marketing. AMZN may evolve to become a bundler of others' content

Tech companies want to be the platform, get info on customers, be gateway,

let others waste money on content.

DIS will be successful.

Direct relationship w/ customer in scale with growth and pricing power is a powerful business model.

DIS knows they need direct consumer relationship.

HBO Max: HBO content budget was $2bn/year.

If you want HBO, you already have it, so not much gain in new customers in the U.S.? Malone doesn't see the growth. Maybe even attrition.

HBO budget is not enough to protect for the long term. Takes years to develop content internationally. Don't own rights to intl distribution. Problem seeing scale at HBO to get to top of direct consumer biz. HBO is the same as it's been for 25 years. If you want it, you already have it so where is the growth?HBO may capture wholesale spread (as big bundle moves to direct).

ATT will face challenges. Historically has been the biggest dog in every fight, but not now, and not in this space (streaming media). About scale and globality. Need global scale, or won't get enough scale to compete in this space. This will be the challenge for ATT, HBO. FANG companies are all global. If you're only in the U.S., how do you compete?

Sports is glue that keeps big bundle together... will eventually blow up. Not sure when... big bundle still overpriced due to sports content...

Content Cost

At some point, hail Mary passes for some will prove to not be working so content cost will moderate. Some will fail (and stop spending) etc...

NFLX will have to moderate spend at some point. Bundling of these services will happen too. Distributors may bundle too, if it reduces churn etc... will evolve like traditional cable. Comcast offers Netflix etc.

Cord cutting will level off. Erosion won't stop completely, though...

Cutting video increases margins at cable companies as margins for broadband is higher. Happening naturally.

Satellite will end up serving people with no other options, rural etc.

Linear TV will lose subscribers, ads, but as you get direct relationships, value of ads go up as you know more about customers. Ad rev potential goes up; more focused ads etc. Have to fight decline in reach due to decline of big bundle. Provide content direct through app and sell content to others etc. Random access via app; if you subscribe to Discovery Channel, you get stuff through app too (not everything).

Cable industry changed when congress changed retransmission constraints; Margins started to go down. Content providers were able to extract more and more...

Will be profitable for people with unique situations, consistent, stable demand, pricing power, level of uniqueness... those businesses ultimately gets regulated.

Discovery

Discovery owns content globally, generating free cash, need to migrate to direct to consumer.

Malone bought more stock this week (November 2019). Discovery will solve issues. Stock is dramatically undervalued. Malone bought $75 mn worth of stock. Growing, generating free cash. Market cap to levered free cash flow, cheapest on screen... They own all their content, generates tons of cash, investment grade b/s, they are growing while others are shrinking (5.5x cash flow). Cheap for good company...

Malone paid $28.03/share.

CBS/VIA

They have no global presence. Lot of content is bought. CBS is totally dependent on sports rights so not sure about long-term profitability. Not sure if CBS has enough power to carry all the channels.

VIA underinvested for many years, bought back stock at high prices, tactical mistake.

How important is MTV, Nickleodean to distributors? Question sustainability of model, and also they are U.S. only.

Yes, stock is historically cheap, but... licensing out content to others. Ice cube melts faster when you don't put content on your own channel.

CBS/VIA needs to get global for long term sustainability. Find niche, glue to make customers sticky. Something unique.

Lions Gate

Sold LionsGate; didn't see them execute strategy of using library/content to drive Starrs. They focused too much on selling content instead of driving their own distribution.

Need global scale, or niche in small area that big guys don't care about to survive.

Wired and Wireless Together

Liberty Global followed strategy based on belief that combination of wired and wireless would lead to synergies. Turned out to be true. Belgium, Holland (combined with Vodaphone). Once they built scale, they were able to acquire. Synergies were real and very substantial.

In U.S, for Charter, same idea. Keep growing until they understand the economics of a combination. At the moment, not far along enough on that path. Once scale is achieved, think about building own network. Hybrid tranmission over time. Could be joint ventures, mergers etc.

Malone interested in Altice, but Patrick wants control etc...

Uber

Not an expert, but doesn't understand Uber, how is scale going to make it profitable? Like selling hot dogs at a loss and making it up in volume. Can't see how scale changes economics. Can't understand why Dara took job.

Politics

Worries about attack on success and wealth in this country.

Worries about where country is going.

If Warren wins, wealth destruction will exceed wealth transfer. Has places in Ireland, Canada, Bahamas etc... (that he can escape to), but Malone rather stay here, be optimistic about balance.

Malone is Libertarian, would vote for Bloomberg.

Trump has right strategy, but not the right guy; he doesn't build a team. A lot of people that worked for him trying to take him down now.

What It Takes, Dimon, Twitter etc.

Date: 2019-11-14Recently, I've gotten some emails asking about the blogger email updates. I googled around (again) recently for a solution and couldn't find one, and also looked at some mass email services and they aren't free over a certain number of subscribers.

So, as has been suggested here by some over the years, I just set up a Twitter account to announce when I have a new post.

My handle is:@brklninvestor

I know many of you are not on Twitter, so I will figure out an email solution too, eventually.

Dimon on 60 Minutes

Jamie Dimon was on 60 Minutesthis past Sunday. He is still one of my favorite CEOs and is great to watch. I thought his response to the question about running for president was pretty funny; "I thought about thinking about it..." That reminds me of one of my favorite Dr. Who lines (from the Eleventh Doctor, Matt Smith), "Am I thinking what I think I'm thinking?"

Anyway, in this environment, there is no way people like Dimon or Bloomberg would gain any traction in the Democratic party. I think either of them would make great presidents, but it just won't happen. No chance at all, unfortunately.

When Lesley Stahl mentioned the bailout of the banks during the crisis, Dimon should have pointed out that it wasn't really a bailout; all the money was paid back with interest (at least the major banks paid it all back). Schwarzman in the book below talks about how he cautioned Paulson about this; to try to avoid the use of the term bailout as it could become a problem if that word stuck. To this day, I still talk to people who think that the banks were "bailed out". They think that the government just gave the banks free money with no strings attached. They are often surprised to hear that the money has been paid back in full, with interest.

Having said that, the definition of "bailout" seems to be to offer financial assistance to an entity on the brink of collapse, so maybe TARP was a bailout. But still...

When asked about CEO pay, Dimon said, "what do you mean?", or something like that. It was clear he was trying to just avoid the question. To say he has nothing to do with his own compensation, while it may be technically true, wasn't really convincing to people who wouldn't understand. He could have just agreed that CEO pay is too high in this country, and that it should be dealt with at the tax level but probably shouldn't be resolved legislatively or whatever. No need to dodge the question. There is nothing wrong with saying that high income people should pay more in taxes (at higher rates), and that some of the crazy loopholes that reduce tax rates for the rich should be closed etc. He is not running for public office, so he is not taking any risk in saying stuff like that.

But anyway, it was nice to see him on 60 Minutes. Although I am progressive on many issues, I find the current anti-corporation sentiment to be unfortunate. Companies can only change their image by their actions. More and more companies are acting like they are the solution rather than the problem, which is good.

Markets

The markets are kind of crazy. I don't mean this rally, necessarily. A lot of this rally is just recovery from last year's drop and valuations are still in a zone of reasonableness, so I am not at all alarmed by it or worried about it.

I mean the way the markets react to every Trump tweet, or nowadays, Elizabeth Warren ideas. I like Elizabeth Warren a lot, actually, even though she seems to hate Dimon and everything Wall Street.

Whenever the markets tank when Warren's poll figures go up, just remember what happened on election day in 2016; the markets freaked out and tankedwhen it realized Trump is going to be our next president. But before the next morning, the market took off and hasn't looked back.

Remember what happened to health care stocks in 1992 (Hillary-care), and 2009 (Obama-care). When widely publicized problems hit the market, it is very hard to predict what will happen. Howard Marks would call reacting to these headlines first-level thinking.

First of all, we don't know if Warren is going to be nominated. Even if she is, we don't know if she will beat Trump. Even if she wins, we don't know how much of her plan can be executed successfully (will she run to the center for the general elections? Will she take a more prudent, realistic course of action once in the White House? I'm not saying her ideas are bad or impractical, but she can calibrate her goals according to the reality she confronts once she's there).

There are so many levels of "unknowns" that it makes no sense, really, to try to discount these things so far ahead.

Anyway, if any of these things move the markets too far in any direction, it's probably a great time to take advantage of it and go the other way.

Growth vs. Value

I hear and read about this all the time, and I totally get it and agree. I am a believer in mean-reversion. On the other hand, there are secular realities hidden in these figures too. For example, Bed, Bath and Beyond (BBBY) is one of my favorite stores and was one of my favorites in terms of management. I followed them closely for years, and eagerly looked forward to their annual reports. But it was always a pretty expensive stock. When it finally started getting cheap, it seemed to have lost it's way.

Maybe I am putting in the bottom in this stock, but these days, it's hard to figure out what this company is trying to be. Not too long ago, you would walk into a BBBY and then, suddenly, in the middle of the store, there would be like a miniature supermarket, with potato chips, cereal and whatnot. I was like, what?

It's like the newspaper business. As Buffett says, if you wouldn't start the business from scratch today, then it's probably not a good business. And if it's not a good business, you probably don't want to own the stock.

Again, I loved BBBY for many years (and it's just luck that it hasn't been a part of my portfolio), but it's hard to think of a reason for it to exist. A lot of what they sell is exactly the sort of thing Amazon is very good at selling, and for lower prices. Stores like Target are also selling similar things for competitive prices, so I guess it's a similar story where Target/Walmart/CostCo and others (Amazon) are killing the category killers; same as CD stores, book stores, toy stores etc.

This is not to say necessarily that we should go long AMZN and short BBBY, JCP and other retailers (well, that's been a great trade for a long time!). It's more of a question about how much of this growth versus value is the usual cyclical thing that will eventually mean-revert, and how much of it is secular destruction of multiple industries (I don't think most retailers will recover).

WeWork/Softbank

This is a fascinating story. I really admire the vision and conviction of Masayoshi Son. He is fun to watch and follow, and I have always wondered when and if I should buy Softbank stock. There were many reasons to buy it, especially the usual discount to the sum-of-the-parts valuation and things like that.

But one thing that has always bothered me was his almost reckless aggressiveness. I guess that's a good thing for someone in that area, but it was always a little too scary for me. I remember watching him in an interview, laughing at the fact that the price of Softbank stock went down 99% (or whatever percentage it was). I don't want the steward of my capital laughing about something like that. It is definitely not funny to me.

Also, the sheer size of some of these investments makes it highly unlikely that they can achieve high rates of return over time. Yes, Alibaba was a huge home run. So was Yahoo Japan and some others. But what were their capitalizations when the investments were made? I don't think they were valued at $40-50 billion. How much money were they losing? Probably not billions. Things are truly insane these days.

Thankfully, that unicorn bubble, at least, seems to have popped for the moment.

Great Book

And by the way, the original intent of this post was about a book. I just finished Schwarzman's book, What it Takes: Lessons in the Pursuit of Excellence and thought it was great. This is not a book you want to be reading in the company of your progressive friends (most of my friends and neighbors are progressive; many are even democratic socialists). Even some conservatives roll their eyes at a guy who throws himself expensive birthday parties and puts his name on library buildings. But I don't care about that. Not everyone has to be like Buffett or Munger.

But what I can say is that after all these years on and following Wall Street, I've mostly heard good things about Blackstone. When they IPO'ed, I followed closely and it was clear that they are a really well-run shop. At the time, Fortress Investment Group was the other private equity firm to go public before Blackstone, and I was really not all that impressed after following them for a while. Their performance was not great, hedge fund was not doing well etc. But Blackstone was at a totally different level.

Whether its their conference calls, presentations, it was all done very, very well.

The only reason I never bought the stock was that, like others, I was worried about the huge increase in AUM at all of these alternative asset managers. How are they going to maintain the high rates of return with ever-increasing AUM and ever-increasing competition, not to mention the corresponding ever-increasing prices? Schwarzman, in the book, makes the case that size has become an advantage for them; they get first call (or are the only call), often because they are the only ones that could close a deal of certain sizes.

I had the chance to grab some shares at under $4.00 during the crisis, but then there were many other things that were cheap too... But still, knowing what a solid shop it was, I shoulda grabbed some shares then. I guess one rule should be that any time a well-run company is trading for the price of an option, one should buy at least some shares!

Special Situations Trade

By the way, I should also mention that these private equity firms are in the process of converting from partnerships to corporations; this expands the range of potential buyers (institutions that wouldn't or can't own partnerships), which would serve to increase liquidity and most likely valuations of these companies.

I know many of us berk-heads think private equity is nothing but leveraging and cost-cutting, but I still think these guys have a high quality shop.

Persistence

One thing that surprised me was how hard it was for Schwarzman / Peterson when they first started up, sending hundreds of letters to investors with no response, visiting potential investors and getting rejected for months on end. This reminded me of what Barbara Corcoran said in an interview once. The interviewer asked her what the difference between a good broker and a bad broker was, and she said the great brokers know how to take 'no'. If they can't close a deal, they move on to the next one and keep going. The bad ones aren't good at taking 'no', and it wears them down; they get discouraged and it impacts them too much to keep going.

I'm sure we've all seen examples of this. A friend once told me a relative wrote a novel, sent it to a publisher and it got rejected and they gave up writing and blames the over-commercialized, corporate-controlled, dumbed-down American culture for their failure as a novelist (and the friend agreed with that). I was a little shocked. So you write one novel, send it to one publisher, it gets rejected and it's all over? Well, I don't know anything about writing novels and have no idea how that world works, so I didn't say anything.

But I was thinking back to the many famous novelists who kept getting rejected from publisher after publisher, writing story after story before getting published. I think Haruki Murakami got published on his first try, but those are probably rare cases.

Going back to Schwarzman, even with his credibility / reputation (and Peterson by his side), they struggled to get Blackstone off the ground. You can imagine how much work it's going to take to get anything done without that sort of advantage.

Having said all that, it is an autobiography so we hear everything from his side. I'm sure there are people with tales out there somewhere he doesn't want told (and this goes for someone like Buffett too!).

But, it's still a good read.

Bubble Yet?

Date: 2019-09-27Bubblicious?

People still speak of bubbles a lot, bubble in the bond market, stock market, unicorns etc. But I still don't really see a bubble except in certain areas of technology. Otherwise, things seem to be in a normal range to me, except interest rates. They do seem a bit low, but having said that, I still see 4% as a decent 'normalized' long term rate for the U.S. (as I have said here before many times).

TheValuation Sanity Check shows the Dow trading at 20.6x current and 16.4x forward P/E, and the Berkshire portfolio (largest holdings) trading at 17.4x and 14.3x their current and forward earnings. Browsing down that page, there is nothing really alarming about anything, really. Some things look expensive, but nothing insane.

Also, here are some charts I plucked off the internet. The first bunch is from the JP Morgan Asset Management's Guide to the Markets. This is a nice report that they put out every quarter, and is fun to flip through.

These charts too show nothing really crazy.

I keep hearing people talk about how crazy it is that the market is up 20% this year, but given that a lot of that is recovering from losses last year, it doesn't sound crazy to me.

Also, people keep saying that the returns of the last 10 years suggests the market is overvalued. But again, given that the much of the returns is recovering from the financial crisis bear market, I think it's irrelevant. If the market had double digit returns over 10 years from a market high, then I would be more inclined to agree; something bad might be about to happen.

But this is clearly not the case here. In fact, from the October 2007 high, the market has gone up less than 6%/year (excluding dividends), and 3.4%/year since the 2000 peak. This is hardly the long term performance figures you see in a real bubble.

I won't look for them, but look at the similar figures for the 2000 peak, Nikkei 1989 peak etc. It is very different from today.

The above forward P/E chart shows a normal range, nothing alarming. Of course, people will argue that the market has been consistently overvalued for the past 25 years so this is not indicative of anything. But interest rates are a lot lower now than in the past too, and this chart doesn't show any abnormally high P/E level due to lower rates. I suppose one can argue about the validity of EPS estimates a year out. That is certainly a valid point.

This X-Y plot of forward P/E ratio versus future returns show potential returns solidly in the positive. I did something similar using Shiller's CAPE ratio and found similar results.

One year forward returns based on P/E

My analysis goes back to 1985, so is longer term than the JPM study (which goes back to 1994), but hasn't been updated (a couple of years shouldn't make a difference!).

Median P/E Ratio

And here's something I found. The S&P 500 is market-cap weighted, so the index P/E ratio tends to be influenced by the large cap stocks. When you have a bunch of large caps that are overvalued, it tends to push up the P/E ratio of the whole index.

To get a more 'typical' P/E ratio of the random stock, a median P/E can be more useful, as half the companies would be more expensive, and half would be cheaper than this level.

I found this chart in Yardeni's September report: Yardeni P/E report

Here's the median forward P/E ratio:

Again, nothing spectacular here. Looking at this (and the other charts), if someone is net short the market, you would have to examine their brains. Why would anyone be net short in a market like this? It doesn't really make sense to me.

Just flip through these charts again, and imagine you are the head of the trading desk at a hedge fund or bank somewhere. And say some guy is massively net short the market. You ask him why he is so short, and he tells you that it's because the market is way overvalued. What would you say? Would you feel comfortable going home and sleeping well? Of course, this trader may contribute to reducing the overall exposure of your desk, but don't think of it that way as you can always adjust your market exposure with futures.

If you think of it this way, it's sort of insane.

The other non-bubble thing is that you don't hear people talking about the market at all. Usually, in a real bubble, people really like to talk about the stock market in situations where that is not normal. A couple of years ago, everyone was talking about bitcoin. I don't hear much about that anymore these days.

Also, the news flow is so negative these days, whether it be Brexit, Trump tweet, U.S./China trade, Iran... Wherever you look, it's just bad, scary news. And yes, the market responds by going down, but it comes right back up. This is not to say that the market will always come back up. We will have a bear market at some point.

But if you are net short and all these 'favorable' developments to your position is not making you money, that's kind of a serious problem. What happens when any of these things resolves itself? What if we do get a blowoff that has happened in most other bubble tops (2007 top was not really a bubble in terms of valuations, so bear markets can happen from normal valuations too).

Value-Growth Gap

The other thing is the huge gap between growth and value stocks. I am not that big a fan of this as the division seems arbitrary and kind of meaningless. But what is encouraging is that despite this slightly higher valuation of the overall market, the gap between value and growth seems to suggest that one can avoid a lot of pain by being more in the value area than growth.

Back in 2000 when the market was actually really overvalued, value investors did fine despite a 50% drop in the S&P 500 index as the drop was driven mostly by expensive companies going down in valuation. I think value stocks actually went up back then.

This may be true this time around too.

Market Timing

Most of us value investors don't believe in market timing at all. It is so amusing to watch the market go down 200 pts (or more) on a tweet only to reverse itself within a day or two by another tweet. Why anyone would trade based on this stuff is beyond me. I am a believer that headlines almost never mark turning points in the market. If the market is making a new high and then plunges on some negative headline, you can bet that that high will not be a high of any significance. I have seen various attempts over the years to analyze peaks and troughs in the market and matching it with news headlines; there usually is no headline that marked the top or bottom of a market.

It's just silly to try to figure out when the next bear market will happen.

There is one thing, though, that I would watch out for. If the U.S. market goes into a situation like the Japanese stock market in 1989, then I would obviously react. I would definitely lighten up equity holdings (still on a case-by-case basis based on valuations, of course) and maybe even consider buying puts, going short or whatever (OK, maybe not as I watched many bears lose a lot of money in 1998-2000 period only for them to be proven right but already having lost too much money made no money on the decline).

In any case, it would be a valuation call; I would lighten up when I can't accept the valuation levels. And it would be by each individual holding, not some vague notion about the directions of the overall market or economy.

Japanification of Markets?

The other worry is the Japanification of global markets. We were all baffled by the low interest rates in Japan for decades, and here we are with multiple countries and trillions of dollars in debt trading with negative interest rates.

Many commentators thought it won't happen here, and yet here we are with long term rates under 2%.

What about the stock market? Can the U.S. go into a bear market like Japan's that lasts 30 years? This sort of thing worries me too a little. We can't say it won't ever happen here as we were wrong about interest rates. Well, I've actually been in the camp of "lower for longer" so am not really all that surprised by how low our interest rates are.

But it would not be fun if the market went into a 30-year bear market.

Here's why I don't think it would happen, at least any time soon:

- The Japanese market went up to 60-80x P/E at the time. That sort of valuation takes decades to grow out of, and it's that much harder when there is no growth! We are nowhere near that kind of valuation.

- The Japanese government and companies spent most of the time since then hiding things rather than fixing them. When the U.S. had a credit crisis, banks were encouraged to raise capital and fix their problems, not hide them.

- Regulations are meant to maintain the status quo, protect large companies (who are contributors to the LDP) etc.

- In Japan, companies are discouraged from right-sizing. They run under a system the Canon CEO, Fujio Mitarai, calls corporate socialism. He says that since the Japanese government doesn't offer much of a social safety net, that burden falls to large corporations; they are strongly discouraged from firing employees. This is why there is a word for this category of employee: madogiwazoku (google it!). Here's an article about it: Boredom Room. It's no surprise that the stock market has been dead for so long with so many zombie employees at zombie companies. This is very different than in the U.S.

There are many other problems, but those are just some big ones off the top of my head... You may think of better reasons why Japan has been stuck for so long.

None of these are true in the U.S. That doesn't mean we can't go into a 30-year bear market, of course. But it just seems to me that it is not likely at the moment.

Hard Left Turn in Politics?

Others worry about the progressive left; Leon Cooperman joked the other day that if Elizabeth Warren gets elected, the market won't open. I understand that fear, and as a big fan of JP Morgan, I totally get it.

I am actually pretty progressive myself (I used to be conservative but have been moving left over time), but I wouldn't worry about this at all.

First of all, we really have no idea what's going to happen. We don't even know who is going to be the democratic candidate; it's possible that someone else not even running now will come up out of nowhere (well, not sure if that's possible, actually, but we still have a long time to go).

We do know that Warren is as progressive as she presents herself, so this may not apply, but it's possible that she runs hard left to take Sanders' and other voters only to run back towards the middle if she wins the nomination.

We don't know what she can accomplish even if elected, right? This is a president, not a dictator. Did FDR or Kennedy destroy the country? I haven't looked at the market action around their elections, but I don't really think there is a big, visible dent or bend in the long term charts based on who was president.

So this is certainly a risk factor, but my guess is that things, as usual, will not turn out the way we expect even if Warren wins the election. It's a complex model and things aren't going to be so easy to predict.

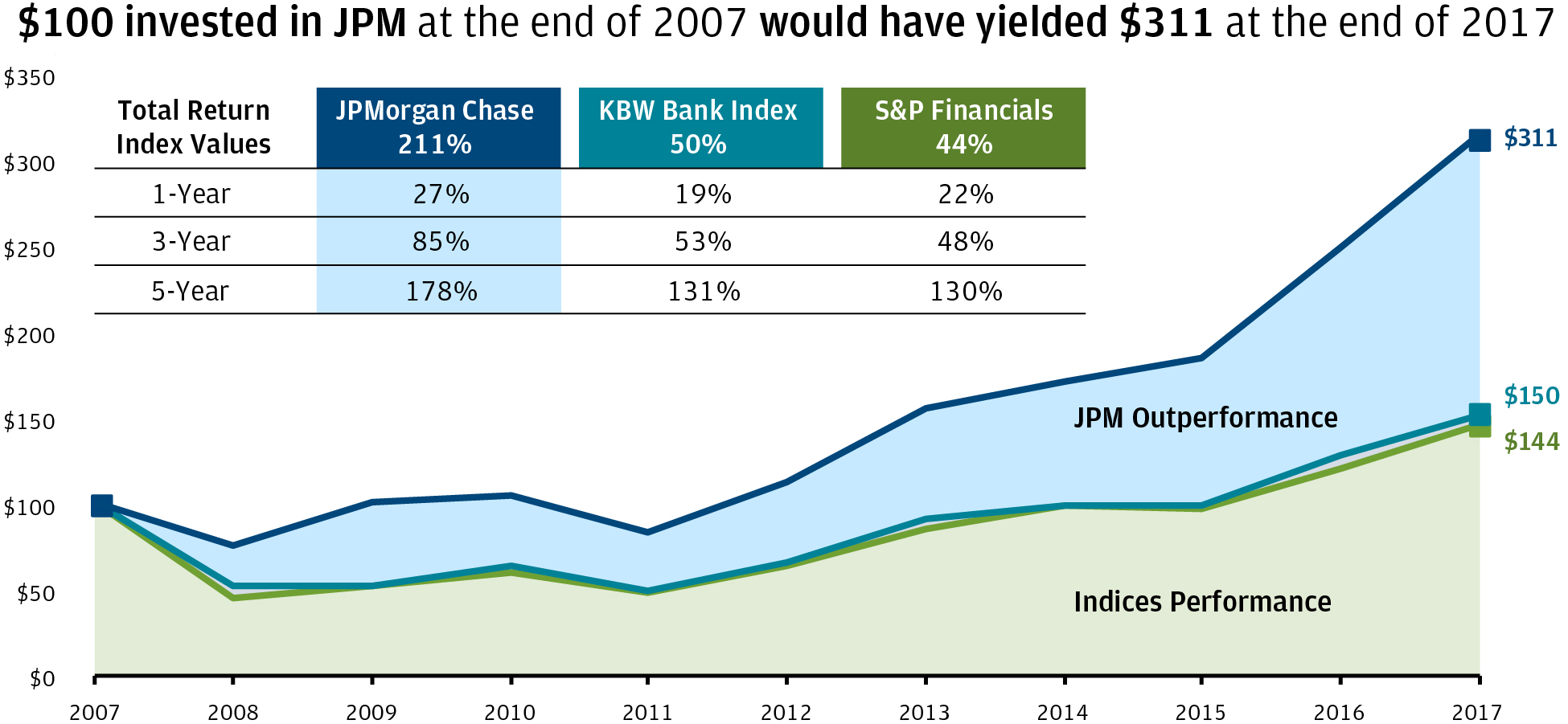

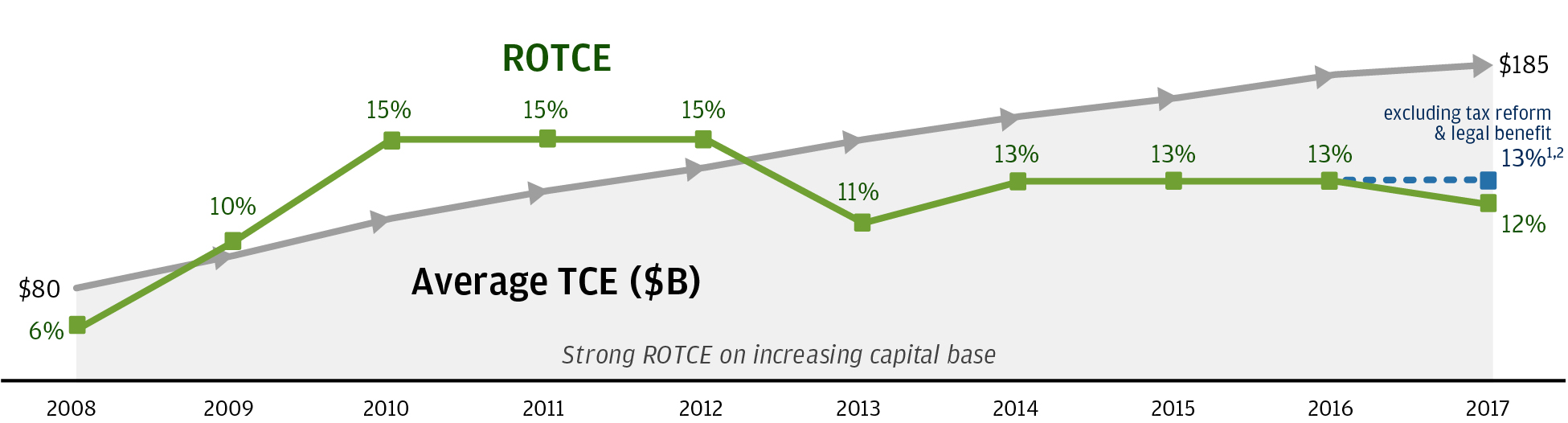

JPM 2018 Annual Report, Website etc.

Date: 2019-04-04JPM's annual report is out, and maybe a good time for another post here. I know it's been a few months. Honestly, I have been coasting recently on what's been working and haven't been digging around too much in the stock market. Most of my time recently has been spent on programming, having taken on a few freelance gigs for fun (and beer money).

Website

Anyway, I have updated my website. A lot of things there were broken, but everything broken there was just due to the Google and Yahoo Finance APIs being shut down completely. This is really annoying. There are a lot of books out there on AI, data science, quantitative finance and all that, and a lot of them depend on those APIs, so it's like those books are worthless now. Well, not really... you just have to find an alternative source of data. But who wants to deal with that hassle?

Anyway, the website is here:brklninvestor.com

The Market Today

One of my favorite pages there is this one:Valuation Sanity Check

People are still talking about how overvalued the stock market is and how it has to go down, and how valuations do matter and that perma-bulls are saying valuations don't matter.

Well, I have been telling people to ignore those people for the past few years, and I, for one, would not say that valuations don't matter. Valuations do matter. The higher the valuation, the lower the future returns. Duh. This is not rocket science. This is no different than bonds. The higher the bond price, the lower the yield, the lower the future return.

Where I disagree with the bears is their conclusion: that if the market is overvalued, then the market must go down. (I am not arguing that markets won't ever go down; they will with 100% certainty. But I doubt anyone can tell us with any consistent accuracy when it will!)

I also quantified this and put the data on the website.

Future returns in an overvalued market

I didn't update it, but since the market has been up, the conclusion would be the same or better. Plus, the analysis uses decades of data, so a couple of years is not going to make a difference.

As for all the worries and concerns, Buffett's 2018 letter has a great section called "American Tailwind", and it basically says that the market has done well over the past 77 years and there were always things to worry about, but the market did pretty well. Maybe more on that in another post.

Anyway, the home page shows the trailing P/E ratio of the S&P 500 index at 21x, and forward P/E of 17x. This may seem high to some of us who started in the stock market business when interest rates were around 8%. They are now much lower than that. I've said in posts that with a "normalized" interest rate of 4% over the next decade, I would not be surprised if the market P/E averaged 25x P/E. So a 21x P/E is not at all alarming or shocking to me, and the 17x forward P/E actually looks pretty attractive, even assuming that forward estimates tend to be over-estimated.

Also, looking at the Valuation Sanity Check page, the Dow 30 stocks seem to be trading at 17.5x 2019 estimates and 15.4x 2020 estimates. The Berkshire stocks (just the stocks listed in the annual report) are trading at 15.4x and 13.4x 2019 and 2020 estimates.

Again, there are issues of the validity of 'estimates', but even still, these figures are nowhere near bubble levels.

My thoughts about the market hasn't changed at all in the past year. Yes, it was a little scary in the fourth quarter of last year, but I was not that particularly worried as none of my work (as shown in previous blog posts) has shown any rubber band stretched to it's limit that must snap back.

OK, anyway, maybe more on that another time. Going on to my next pet peeve...

Data